Two paintings of the XIX century about the "Princes in the Tower", showing young Edward V and his brother Richard, Duke of York

Bosworth

~22 Aug 1485~

The Wars of the Roses was effectively an argument between two lines of the same family.

Edward III (1327-1377) died of a Stroke. His third son John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, had dominated the government during his last years, but Edward was succeeded by his grandson Richard II, only son of Edward, the Black Prince.

Richard was deposed in 1399 and murdered; and was succeeded by Henry IV, another grandson of Edward III by John of Gaunt.

Henry IV was succeeded by his son and later his grandson, Henry V and Henry VI. This was the House of Lancaster.

Edward IIIís second son was Lionel, Duke of Clarence. His line had not succeeded to the throne after the deposition of Richard II because it was only represented by a single female. His grand daughter, lady Anne Mortimer, married a son of Edmund, Duke of York, the fourth son of Edward III. This was the House of York.

By the time Henry VI succeeded to the throne at the age of 8 months this Yorkist line was in the ascendancy and when Henry began to suffer from bouts of madness the senior member of this line, Richard, Duke of York, served as Protector. Richard was next in line to the throne after Henry and his son Edward but decided to attempt to force the issue and by 1455 open warfare had broken out between the two camps.

Richard himself was killed at the Battle of Wakefield in 1460 but his son Edward inflicted a serious defeat on Henryís forces at Towton in 1461 and the King was forced into exile.

Edward was crowned Edward IV and reigned until a coup in 1469 when Henry was returned briefly to the throne by the Earl of Warwick, called "the Kingmaker". Edward returned from exile in Burgundy in 1471 and regained the throne. At this point Henryís son Edward was murdered and Henry himself was killed soon after.

Edward IV died in 1485. His son, Edward V, was only twelve years old, so Edward IV had designated his brother Richard as Protector. Richard had Edward's two sons taken to the Tower of London, where they vanished, so Richard was proclaimed king as Richard III. It is not known what actually happened to the boys, but most likely they were killed. The mystery remains as to who killed them, and if it was done on Richard's orders or if it was Henry who did it.

|

Two paintings of the XIX century about the "Princes in the Tower", showing young Edward V and his brother Richard, Duke of York |

Richard III had exiled Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond, the recognised head of the Lancastrian cause against Richard's House of York. Henry gathered allies abroad, and, buoyed by Richard's dubious support in England, effected a landing near Milford Haven on 7 Aug, with about 2,000 French mercenaries and a handful of Lancastrian lords and knights. He gathered reinforcements as he marched through Wales, then through Shrewsbury, Stafford and Atherstone.

By May, Richard had left London for the last time and journeyed to Windsor. His Knights and Esquires of his Household accompanied him. Francis, Viscount Lovell, was sent to Southampton to lead the forces in case Tudor landed in the southern counties. John, Duke of Norfolk, was stationed in Essex. Sir Robert Brackenbury, the Constable of the Tower, was defending the capital.

Richard left Windsor and departed for Kenilworth. By the middle of Jun, he was at the centre of his realm at Nottingham Castle. He sent his niece, Elizabeth of York, along with her sisters, his nephews and his illegitimate son, John of Gloucester, to Sheriff Hutton. From Nottingham, he sent instructions to the commissioners of array in all the shires alerting them to the invasion.

Richard had every reason to believe that he had sufficient manpower to deal with Henry's army. Richard had a high turnout of nobles. The ballad's author listed the names of 90 supporters of Richard at the battle; 23 of whom were nobles, and the rest gentry.

Then the King sends messengers to every nobleman and knight in the realm, and assembles a company of unprecedented size:

Thither came the

duke of Norfolk upon a day,

and the earl of Surrey that was his heir;

The earl of Kent was not away,

The earl of Shrewsbury brown as bear.

The ballad continues in similar fashion to list the nobles who swore to support the king; the earls of Lincoln, Northumberland, Shrewsbury, Kent and Westmorland, Lords Zouche, Maltravers, Welles, Grey of Codnor, Grey of Powys, Audley, Berkeley, Ferrers of Chartley, Dudley, Lovell, Fitzhugh, Scrope of Masham, Scrope of Bolton, Dacre, Ogle, Lumley, and Greystoke. There follows a list of other knights who were in attendance, including the following clearly identifiable persons: Ralph Harbottle of Beamish, Henry Horsey, Henry Percy, John Grey, Thomas Montgomery of Faulkborn, Robert Brackenbury of Denton, Richard Charlton of Edmonton, Thomas Markenfield of Markenfield, Christopher Ward of Givendale, Robert Plumpton of Plumpton, William Gascoigne of Gawthorpe, Marmaduke Constable of Somersby, Martin De La Sea, John Melton of Ashton by Sheffield, Gervase Clifton, Henry Pierrepoint of Holme Pierrepoint, John Babington of Dethick, Humphrey Stafford of Grafton, Robert Ryther, Brian Stapleton of Carleton, Richard Radcliffe of Derwentwater, John Norton, Thomas Mauleverer of Allerton Mauleverer, Christopher Moresby of Windermere, Thomas Broughton of Broughton in Furness, Richard Tempest of Bracewell, Ralph Ashton of Ashton Under Lyne, Robert Middleton of Dalton, John Middleton of Belsay, John Neville of Liversedge, Roger Heron, James Harrington of Brearley, Robert Harrington of Badsworth, Henry Vernon, Robert Manners of Etal, Thomas Strickland of Sizergh, William Parker of London, John Paston, Robert Percy of Scotton, Thomas Windsor of Stanwell, Geoffrey St. Germain of Broughton, John Sacherverel of Morley, Juan de Salazar, William Sapcote of Thornhaugh, William Staffertone of Windsor, Gilbert Swinborne of Nattertone, Percival Thirlwall of Thirlwall, Roger Wake of Blisworth, John Walsh, Richard Watkins, Richard Williams, Andrew Ratt, John Ratte, Richard Revel of Ogston, John Pudsey of Arnford, Thomas Poulter of Downe, William Musgrave of Penrith, Robert Mortimer of Thorpe le Soken, Thomas Metcalfe, Christopher Mallory of Studley, Thomas Kendall of Smisby, John Kendal, John Joyce of Windsor, John Huddleston, Walter Hopton, Thomas Gower of Sittenham, William Gilpin of Kentmire, Edward Franke, John Ferrers, John Conyers of Hornby, William Conyers, William Clerk, William Catesby of Ashby St. Legers, John Buck of Harthill, William Brampton, William Bracher, Richard Boughton of Lawford, William Berkeley of Uley, Humphrey Beaufort of Barford St. John, John Audley of Markeaton, William Allington, and Thomas Pilkington of Pilkington. A number of hypothetical reconstructions can be made from the two garbled renderings of the same name: Henry Bodrugan alias Bodringham ['Bowdrye', 'Landringham'], Robert Rither ['Ryder', 'Rydyssh'], Robert Oughtred of Kexby ['Utridge', 'Owtrege'], Alexander Baynham ['Fawne', 'Haymor'], John Huddleston ['Hurlstean', 'Adlyngton'].

Colin Richmond, however, quotes the same ballad as showing that hardly anyone fought for Richard. Richmond estimated that only six peers turned out for Richard, several for Henry, and the rest stayed home (Richmond, in Hammond, p. 173). Richmond points out that many of those present at the battle did not fight, and many of Richard's northerners may have been in the Earl of Northumberland's inactive ranks. In his opinion, "[w]hat, therefore, principally happened at Bosworth was the desertion of king Richard". A. J. Pollard, on the other hand, thinks Richard had the support but lost the battle because he charged Henry Tudor's ranks too soon (Pollard, p. 172).

The men who were present at Bosworth on Henry's side were: John De Vere, Earl of Oxford; Jasper Tudor, Earl of Pembroke (created Duke of Bedford); Giles, Lord Daubeney; Thomas Lord Stanley of Lathom; George Stanley, Lord Strange; John Lord Welles of Maxey; Bernard Stuart, 3rd Siegneur of Aubigny; Adam ap Evan; Sir Thomas Arundel of Lanherne; Richard Ashton; Richard Bagot of Blithfield; Sir William Berkeley of Beverstone (knighted by Henry VII); John Bicknell of South Perrott; Sir James Blount of Tutbury; Sir Thomas Bourchier of Horsley; Sir William Brandon of Soham; Sir Reginald Bray of Eaton Bray; Alexander Bruce (created Valet of the Royal Chamber under Henry VII); Arnold Butler of Dunraven; John Byron of Clayton; Sir Edmund Carew of Mohunís Ottery; William Case of South Petherton; Philibert De Chandee of Brittany; William Chetwynd of Ingestre; Sir John Cheyne of Falstone Cheney (created Lord Cheyne after Bosworth); Sir Richard Corbet of Moreton Corbet; Humphrey Cotes of Cotes; Sir Edward Courtnenay of Tiverton; Piers Courtenay; Bishop of Exeter; Matthew Cradock of Caerphilly; John Crokker; Sir Simon Digby of Coleshill; Hugh Eardswick; Sir Richard Edgecumbe of Cotehele; Sir John ap Ellis Eyton of Ruabon; Sir John Fortescue of Ponsbourne; William ap Griffith ap Robin of Cochwillan; Sir Richard Guildford of Cranbrook; Sir John Hallwell of Bigbury; Edmund Hampden of Hampden; Sir Robert Harcourt of Stanton Harcourt; John Hardwick of Lindley; Reginald Hassall; Thomas Havard of Caerleon; Sir Walter Herbert of Raglan; Phillip ap Howel; Richard ap Howel of Mostyn; Sir Walter Hungerford of Heytesbury; Thomas Iden of Stoke; Sir Roger Kynaston of Hordley; Sir Nicholas Latimer of Buckland in Duntish; Thomas Leighton of Stretton en le Dale; Sir Piers Legh of Lymm; Morris Lloyd of Wydegada; Thomas Lovell of Barton Bendish; John ap Meredith of Clenenney; Sir Thomas Milbourn of Salisbury; Sir John Morgan; Sir John Mordaunt of Turvey; John Mortimer of Kyre Magna; Edmund Mountfort of Coleshill; David Myddleton of Denbigh; John Mynde; Richard Nanfan of Threthwell; William Norris; Sir David Owen of Cowdray; Sir James Parker; Sir Thomas Perrott of Haroldston; Sir Hugh Pershall of Knightley; David Phillip of Thornhaugh; Phillip ap Rhys; Ralph Ponthieu; Sir Edward Poynings; Robert Poyntz of Irton Acton (appointed Sheriff of Southampton under Henry VII); Rhys Fawr ap Maredudd of Voelas; Richard ap Howell; Sir John Risley of Laenham; Rydderch ap Rhys of Cilbronnau; Sir Brian Sandford of Thorpe Salvin; Sir John Savage of Clifton (knighted; granted lands from attainted Yorkists); Sir Charles Somerset of Chepstow; Sir Humphrey Stanley; Sir William Stanley of Holt (created Chamberlain of Henry VIIís household); Sir Gilbert Talbot of Slottesden (knighted; granted lands from attainted Yorkists); John ap Thomas of Aber Marlais; Rhys ap Thomas of Newton Carmathenshire (awarded Crown lordship of Brecknock and Chamberlain of Carmarthen and Cardigan); Sir Roger Tocotes (created Sheriff of Wiltshire under Henry VII); Sir John Treffry of Fowey; Sir Richard Tunstall; John Turberville of West Knighton; Sir William Tyler of Snarestone; Sir Christopher of Urswick of London; Roland De Veleville; Henry De Vere of Great Addington; John Waller the Younger; John Williams of Burghfield; William Willoughby of Broke; Sir Robert Willoughby of Beer Ferrers (granted Receivership of the Duchy of Cornwall and appointed Steward of all mines in Devonshire and Cornwall); Sir John Wogan of Wiston; and Sir Edward Woodville.

The Battle

Richard sent word to Northumberland, Brackenbury, Lovell and Norfolk commanding them to join him in Leicester. On Friday, 19 Aug, Richard left Nottingham and traveled south toward the city of Leicester. On 20 Aug, Richard was in Leicester with his captains mustering his men. By late afternoon, he learned from his scouts that the army of Lord Stanley was at Stoke Golding while William Stanley was at Shenton. Henry Tudor and his men were at Atherstone. On Sunday, 21 Aug Richard and his royal army left the city of Leicester. Richard and his commanders took their position on Ambion Hill at Bosworth Field.

The Earl of Northumberland and Lords Thomas and William Stanley, along with their troops, waited out the start of the battle while the rest of Richard's army engaged Henry's exiles and French mercenaries.

After Richard's commander, the Duke of Norfolk was killed, Richard tried to win the conflict by a surprise charge at Tudor. Richard's left wing, under Henry Percy, fourth Earl of Northumberland, refused to fight. Northumberland - perhaps motivated by jealousy stemming from Richard's northern power and popularity - failed to muster loyal troops and waited on the sidelines during the battle. Four years after Bosworth, the Earl was murdered during a tax revolt, killed by northerners who "'bore a deadly malice against him for the disappointing of King Richard at Bosworth Field'". (Pollard, p. 171) But Charles Ross raises the intriguing possibility that Northumberland was unable to engage Henry Tudor's troops due to the terrain (Ross, pp. 221-223). Thus, Richard III may have charged Henry Tudor's position before Northumberland was ready to help.

To the north waited a third 6,000-man army led by Thomas and William Stanley who had not yet committed to either side. Lord Stanley had married, as second wife, Lady Margaret Beaufort, mother of Henry Tudor. During the battle, in which it seemed Richard was going to be victorious, Henry broke away from the fighting to speak face to face with the Stanleys. His goal was to try to convince them to fight for him. As he was riding with 50 of his soldiers towards the Stanleys, King Richard charged the small group with his cavalry, hoping for a quick victory. It was because of the loyalty and bravery of those 50 men that Henry survived.

Richard killed Tudor's standard bearer, William Brandon, and a giant of a man named Sir John Cheyney. When Richard was only a few feet away from Tudor, Stanley's army moved, surrounding and killing Richard and the men of his Household. As he swung his battle-axe, he was known to have shouted "Treason - Treason - Treason" as he was slain. Northumberland and his army remained waiting on the sidelines and never engaged in battle to assist Richard. The Stanleys committed their men to Henryís cause, and so, Henry was victorious.

Whatever else has been said of him (most of it negative propaganda by later Tudor "historians") no one can accuse Richard III of cowardice. He fought bravely to the end, and was eventually killed on the field, deserted by his friends and allies. Tradition say that after Richard III was "most piteously slain" and the Battle of Bosworth Field thus concluded, that Richard's crown was found where it had fallen -- beneath a hawthorne bush near the small well-spring known as King Richard's Well, marked by a shoulder-high piece of stonework that partially shields the well. The crown allegedly found there was presented to Henry Tudor, on whose head it was placed.

Richard III's naked body was displayed for two days at Greyfriars. Sir Humphrey Stafford with his brother Thomas, and Francis, Lord Lovell, amongst others, fled to St. John near Colchester in Essex. When Henry Tudor marched north, Sir Humphrey came out of hiding and attempted to raise the country against him. Henry forcibly took Sir Humphrey from sanctaury and he was executed for treason at Tyburn in 1486. He was later buried at Greyfriars' in Leicester.

Bosworth Field was the penultimate act of the interminable Wars of the Roses. A minor skirmish two years later at Stoke was a feeble last gesture of defiance from the defeated Yorkists. Henry Tudor became Henry VII, first of the Tudor dynasty, and a new era began in English history.

Henry VII's treatment of the Earl of Northumberland after the battle certainly does not suggest any special favors or gratitude: Northumberland, along with the earls of Westmoreland and Surrey, was taken into custody and kept in prison for several months, being released only under strict conditions of good behavior. This is in marked contrast to the lavish treatment given to Lord Stanley for his betrayal of Richard.

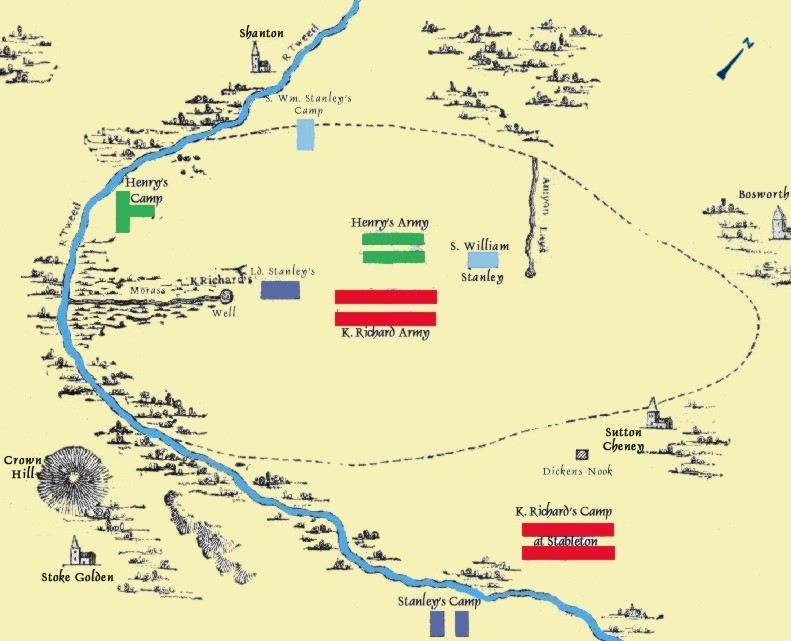

An old plan of the battle. This orientation is considered to be incorrect.

It is possible that the Battle of Bosworth was not even fought at Bosworth. Dadlington, a town about one and a half miles to the south, is a strong candidate for the actual battle site. The earliest sources call the battle's location "Redemore", which is derived from an Old English phrase meaning "reedy marshland", and a document from 1209 (now lost) refers to Redemore as being in the fields of Dadlington. Furthermore, the greatest number of human skeletons, arrowheads, and pieces of weapons and armor from the battle have been dug up in the area of Dadlington/Stoke Golding rather than Ambien (or Ambion -not even the spelling of the name of this site is undisputed-) Hill, the traditional site of the struggle. In 1511, the Chapel of St. James in Dadlington petitioned for a chantry foundation, since the bodies of the men who died in the conflict were buried there. According to William Burton, a local 17th century historian, the battle was christened "Bosworth" after the most notable town in its vicinity, much in the same way the Battle of Agincourt got its name from a nearby castle. This issue still divides traditionalists (those who think the battle was fought at Ambien Hill) and revisionists (the Dadlington crew). Some historians have accepted a compromise scenario in which the battle starts out at Ambien Hill and moves into Dadlington when the Yorkists are routed.

to Life Page

to Life Page |

to Home Page to Home Page |