BARKING ABBEY

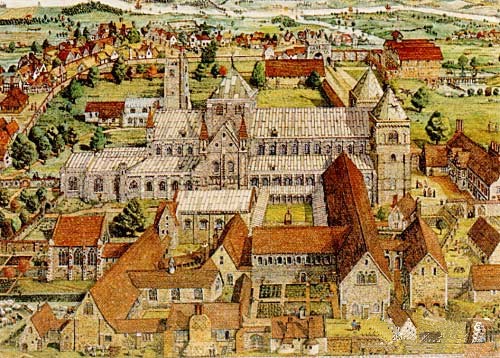

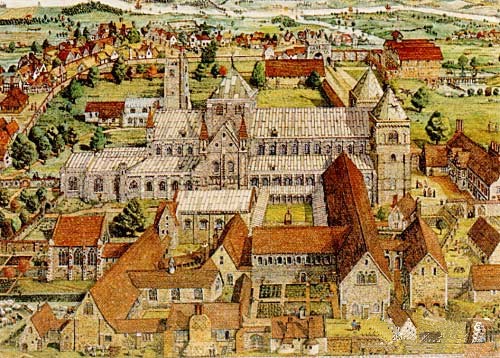

Barking emerged as one of the most important towns in the country with the founding of the Abbey in A.D.666. The Abbey was one of two monasteries founded by Erkenwald, Bishop of London, one for himself in Chertsey (Ceortesei), and one for his sister Saint Ethelburga in Barking, where she was installed as the first Abbess, the new monastery was dedicated to St. Mary, and quickly endowed by the Christian East Saxon princes with land and property, most of which was to become the Manor of Barking, with boundaries the same as those surrounding the former municipal boroughs of Barking, Ilford and Dagenham. This, the oldest estate in Essex, remained a viable entity until the railway brought London rolling eastwards. Erkenwald's strong Romanising influence in the See of London was felt for centuries after his death and inspired a flourishing growth in the community at Barking.

The first Abbey was a missionary centre and was destroyed by the Vikings in 870. All that remains of the first Barking Abbey is a broken Saxon Cross. Equally obscure is the restoration of monastic life after King Alfred's son, Edward the Elder, had driven the Danes out of western Essex in the early 10th century: the first record is of property bequeathed to the Abbey in 951.

The original Barking foundation was a double (though not mixed) monastery of both men and women under an Abbess, not unusual at that time. Theodore, Archbishop of Canterbury, disapproved, but it was left to Archbishop Dunstan 300 years later to introduce reforms making Barking a strict Benedictine nunnery, the greatest in the country and the only early Saxon monastic foundation in Essex to survive until the Dissolution.

One hundred years later the Abbey was re-founded as a Royal foundation. This allowed the King to nominate each new abbess on the death of the old. Under royal patronage, queens, princesses and members of the nobility all became abbesses. The Abbey became a suitable place for members of the royal family to stay, and in 1066 the first Norman King, William I spent his first New Year since the Conquest here. While staying here he confirmed the Abbey in all its possessions and received the submission of the northern Earls: Edwin of Mercia, and his brother Morcar of Northumbria.

At the time of the Domesday survey in 1086 the Abbey's possessions were widespread. In addition to the titular Manor of Barking, lands and property were owned in other parts of Essex, Middlesex, Buckinghamshire, Bedfordshire and Surrey; twenty-eight houses and half a church (All Hallows by-the-Tower) were owned in London.

The Abbess of Barking enjoyed precedence over all other abbesses, ranking as a baron ex-officio. But the king claimed his due: with the office of abbess in his gift the king was apt to use his powers to appoint his wife or daughter abbess when a vacancy occurred. Henry I's Queen, Maud, was Abbess for some years before her death in 1118, and her niece, also Maud or Matilda, wife of Stephen, was Abbess for a time after 1136. Henry II appointed his daughter, another Maud, in 1175 after the death of Mary Socket, whom he had been persuaded to appoint to the office after her brother's martyrdom.

King John's surrender to the Pope in 1213 brought about a change of procedure. After some skirmishing the principle was re-established that the nuns should elect their own abbess, who would then be granted (often tardy) royal recognition. Thus John's own daughter, yet another Maudor Matilda, was elected Abbess in 1247 and afterwards received the assent of her half-brother, Henry III.

This did not stop the King from delaying confirmation of an election while arrogating to himself the Abbey income. The Abbey was obliged to provide board and lodging for sundry royal servants and hangers on, aristocratic invalids, and political prisoners and hostages.

Among the latter was Robert the Bruce's second wife, Elizabeth, who after her husband's defeat at Dairy in 1306 was detained at Barking with other Scots prisoners until Mar 1314, when she was sent to Rochester Castle for greater security during the preparations for the invasion of Scotland, ending with Bruce's victory at Bannock-burn on 24 Jun. Catherine Sutton was Abbess of Barking (fl. 1363-76). And also Anne Segrave (d. ABT 1377), dau. of Lord Seagrave and grand-daughter of Thomas Plantagenet of Brotherton, who was succeded by her first cousin, Matilda Montague (b. 1350 - d. 1394), dau. of Edward, 3° B. Montague.

The following century the sons of Catherine of Valois and Owen Tudor, Edmund (later Earl of Richmond and father of Henry VII) and Jasper (later Earl of Pembroke and Duke of Bedford), aged about six and five years respectively in 1436 when their mother retired to Bermondsey Abbey shortly before her death, were placed in the care of the Abbess for about four years until considered old enough for their education to be continued by priests. Such impositions, together with recurrent flooding of Abbey lands and other disasters, dissipated resources.

Consequently in 1302-3 the Abbess, Anne de Vere, was ex-communicated for non-payment of Papal tithes, and in 1319 royal permission was obtained for the felling of 300 forest oaks for the urgent repair of the Abbey church and other dilapidated Abbey buildings. High tides again in 1409, sweeping through or over the river walls, flooded 600 acres of meadow in Dagenham marsh, and destroyed 120 acres of wheat in another marsh. An early 15th-century Ordinale sets out the complete calendar of the Barking liturgy and lays down procedure for all ceremonial occasions. The focus of communal life was the Abbey church, one of the largest in the county. In this century, Barking had Catherine De La Pole, dau. of the second Earl of Suffolk, as one of the Abbess.

Barking escaped the first wave of suppression in 1536, enjoying an annual income of £1,080 gross and £862 12s. 54d. net, well above the £200 minimum required to escape dissolution. But the nuns had no illusions about the ultimate fate of their house and could only angle for time to make the best bargain possible for themselves.

At the time of the dissolution, there were thirty one nuns in the community at Barking. Dorothy Barley, who had been abbess since l527, was forty nine years of age and twenty one years professed. Nearly half of her comnuninity must have been middle-aged women. Twelve of them, namely Thomasina Jenney, Margaret Scrope, Agnes Townshend, Dorothy Fitzlewis, Margery Ballard, Martha Fabyan, Ursula Wentworth, Joan Drury, Elizabeth Wyatt, Agnes Horsey, Susan Sulyard and Margaret Cotton, had taken part in her election. Of these, the first four were already professed, and the last a novice in 1499. Gabriel Shelton, Margery Paston and Elizabeth Badcoek were novices at the time of her election and were professed, together with Anne Snowe, Agnes Bucknam, Margaret Braunston, Elizabeth Bainbridge and Catherine Pollard in 1534. Mary Tyrell had also been a novice in 1527, but she must have been professed earlier than the rest.

Dorothy Barley, the last Abbess, sister of Henry Barley of Albury, was fortunate in having a personal friend in Sir William Petre, the young lawyer from Devonshire making his fortune in the King's service. His sister-in-law was a nun at Barking, and the Abbess herself was godmother to one of his daughters. So when the expected happened it was of great good fortune that the King's Commissioner receiving the deed of surrender from the hands of the Abbess on 14 Nov 1539 was Sir William Petre. The Abbess and thirty nuns assembled for the last time in their chapter house to execute and hand to Dr. Petre the deed of surrender, ostensibily a spontaneous act. Among those who signed away their abbey, church and all their corporate possessions were ladies of such well-established Essex families as Fitzlewes, Mordaunt, Tyrrell, Wentworth, Drury, Sulyard and Kempe.Within a fortnight the nuns were given pensions, graded according to rank and age, and sent home. Dorothy Barley got a pension of £133 13s. 4d., one of the largest awarded to the head of a nunnery (the other was for Elizabeth Zouche, Abbess of Shaftesbury). Nuns like Margery Paston, daughter of Sir William Paston of Norfolk; and Gabrielle Shelton, daughter of Sir John Shelton, returned to their family homes. Demolition of the Abbey buildings began in Jun 1540 and went on for eighteen months. For almost 400 years the Abbey site was used as a quarry and a farm.

The road to Creekmouth was repaired and much of the stone carted to luggers and shipped down the Thames for building the King's new house at Dartford. Lead from the roof went up river to repair the roof of Greenwich Palace. To the King's jewel house went 3,586 ounces of silver plate, mostly gilt, and a beryl-decorated silver gilt monstrance weighing 65 ounces. Cattle, etc., were sold for £182 2s. 10d.

Almost all that remained of the old Abbey buildings was the (still standing) Curfew or Fire Bell Gate (rebuilt about 1460), with its 12th- or early 13th-century stone rood in the upper storey chapel, and the North-East Gate (demolished about 1885). Some Norman masonry from the Abbey seems to have been re-used in the outer north aisle of St. Margaret's parish church.

Early in 1911 an excavation was carried out jointly by the Town Council and the Morant Club under Sir Alfred Clapham. Remains of the walls of the Abbey church were left exposed to view and the lines of the cloister out in 1966, 1971, and from 1984 onwards. In 1910 the ruins of the main Abbey church were excavated and became a small park. However the classic excavations by Clapham failed to find the Saxon remains, so it was a great surprise when recent rescue excavations, just outside the medieval abbey precincts, discovered the workshops of the Saxon Abbey.

There were numerous high quality objects, including this fragment of a bone comb, decorated Saxon-style with the head of a horse. The excavators also found part of the leet of a horizontal mill, and most surprising of all, the foundations of a glass furnace dated to around 900, producing very high quality glass.

It would appear that these were the workshops producing the high quality goods that an abbey would need in a society still dominated by gift exchange.

The Curfew Tower is the only section of Barking Abbey that is not in ruins. It was originally built in 1370 and has been extensively repaired, most recently in 2005.

to Life Page

to Life Page |

to Home Page

to Home Page |